America’s Fatal Friendship plus other risks to global prosperity

Thoughts on Trump’s not-so-splendid little trade war, Europe’s growing pains, the costs of Merz’s broken firewall, is France about to get a budget at last, and all hail the Jevons Paradox

A warm welcome to all new subscribers and particular thanks to those who have become paid subscribers. Your support is hugely appreciated. This post is free to read so please do share with anyone you think may be interested. I will be in Brussels next week and look forward to seeing some of you there. Do get in touch if you would like to meet! In the meantime, I look forward to your comments and feedback on this week’s newsletter.

In this newsletter:

Trump’s Tariffs: America’s dangerous friendship

Europe’s Growing Pains: Will a compass help?

Merz’s Bad Bet: Counting the cost of a broken firewall

A French budget at Last? Make or break for Bayrou

Definitely Not an AI Bubble: Welcome to the Jevons Paradox

1. Trump’s Not-So-Splendid War

And so it begins. Donald Trump on Saturday signed the executive orders to launch the trade wars that he has long made clear are going to be the centrepiece of his second presidency. Canada and Mexico will be hit with immediate 25 per cent tariffs on pretty much everything except oil exports which will face a 10 percent tariff. Chinese imports will be hit with an extra 10 per cent tariff. As the Wall Street Journal notes, the scale of these tariffs in dollar terms goes far beyond anything Trump imposed in his first term:

Canada and Mexico combined supplied about 28% of U.S. imports in the first 11 months of 2024, according to Census Bureau data. China accounted for an additional 13.5%.

Trump says that he has imposed the tariffs in response the flood of illegal immigrants and fentanyl coming into America across its northern and southern borders. That has raised hopes that it is all just a negotiating tactic designed to secure better trading terms for the US - better, that is, than the terms the US already has under the US-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCTA) that Trump himself negotiated in his first term. This was what Goldman Sachs had to say on Friday, ahead of the formal announcement:

We continue to think that a sustained 25% across-the-board tariff on Canada and Mexico is unlikely, though these comments increase the risk. Instead, we still believe the floated tariffs are intended to lead to a negotiated policy on immigration and border control. We note comments a day earlier (Jan. 29) in the Senate Commerce Committee from Howard Lutnick, nominated to be Commerce Secretary: “the short-term issue is illegal immigration and worse even still, fentanyl…so, this tariff model is simply to shut their borders…to create action from Mexico and action from Canada, and as far as I know, they are acting swiftly and if they execute it there will be no tariff, and if they don’t, there will be.”

But it is hard to see what more Canada and Mexico could do to disrupt the fentanyl trade hat would satisfy Trump. Trump himself appeared to suggest that he would only know that they had done enough would come when the number of Americans dying of fentanyl poisoning started to fall. In any case, as Paul Krugman says, it is hard to believe that fentanyl is the real reason:

I think you have to see “fentanyl” in this context as the equivalent of “weapons of mass destruction in the runup to the invasion of Iraq. It’s not the real reason; Canada isn’t even a major source of fentanyl. It’s just a plausible-sounding reason for a president to do what he wanted to do for other reasons — George W. Bush wanted a splendid little war, Donald Trump just wants to impose tariffs and assert dominance.

Trump looks certain to get his own splendid little trade war. Justin Trudeau has already said that Canada will be retaliating with $100 billion of tariffs on US imports; Mexico and China have said they too will retaliate Meanwhile Trump has confirmed that the European Union is next in line for tariffs because it has “treated us so terribly”. And that is before any across-the-board tariffs of up to 20 per cent on all imports that it now seems pretty clear are coming.

How things play out from here may depend on the market reaction. Almost all economists agree that a prolonged trade war is likely to lead to higher US inflation, leading to higher bond yields and a stronger dollar. But if, in common with Goldman Sachs, the prevailing view is that these tariffs are a negotiating tactic and likely to prove short-lived, then the market reaction may be muted and Trump will surely only be emboldened. Let’s see what happens on Monday.

Either way, all this adds a new urgency to the informal meeting of European leaders at a dinner on Monday to which Sir Keir Starmer has been invited. This was billed as an opportunity to discuss the way forward for European defence in the context of Trump’s demands that they raise their defence spending to 5 percent of GDP and goal of delivering a ceasefire in Ukraine. Now the leaders must confront the prospect of a trade war with their closest ally.

As Henry Kissinger is supposed to have said, “it may be dangerous to be America’s enemy, but to be America’s friend is fatal”.

2. Europe’s Growing Pains

If Europe is about to find itself embroiled in a trade war, then the most important thing Europeans can do is to redouble their efforts to revive their own moribund economies, better to withstand the impact. So it was no surprise that on the same day last week, both the British government and European Commission set out their plans for how they propose to revive growth and restore competitiveness.

In the UK’s case, that took the form of a much-anticipated speech by Rachel Reeves, which garnered plenty of media attention. In the EU’s case, it took the form of the “Competitiveness Compass”, a 27-page document setting out the new Commission’s legislative priorities for reviving growth over the five years of its mandate. This received very little attention outside the Brussels bubble.

Yet it is the EU’s Compass that is likely to define the long-term prospects for the continent’s economy in the coming years. Politico provides an excellent analysis of its main elements here. At its core are plans for significant deregulation and cutting of red tape. That includes an Omnibus bill due later this month that will scale back green reporting requirements that the EU only introduced last year.

Much of the rest of the Compass sets out how the Commission intends to implement Mario Draghi;s recommendations on how to revive the EU’s competitiveness. That includes plans to reduce EU energy prices through big investments in transmission grids, strategies to boost digitisation and foster European innovation and AI development, deepen the EU’s capital markets, reform EU competition rules and introduce Buy European provisions.

What Reeves’s speech and the Commission’s Compass had in common is that much of the content was familiar. Reeves’s growth strategy consisted of a long list of infrastructure projects previously promised by Tory governments. Meanwhile Commission plans to establish a capital markets union - now rebranded as a savings and investment union - and an energy union have been knocking around Brussels for years. So too has talk of a 28th regime, revived as an alternative corporate legal framework to overcome fragmented national markets.

Reeves is counting on a large Labour majority less beholden to vested interests to succeed where the Tories failed, though few of her projects will be delivered in time to deliver any boost to growth in the current parliament. Brussels is counting on the threat of global economic chaos to overcome the long-standing resistance of national governments to deeper integration and handing more powers to the Commission. But is Europe now too weak, leaderless, and at the mercy of right-wing nationalists to reap the benefits of single market scale?

Meanwhile what was missing from Reeves’s speech was a commitment to Britain’s own deeper integration with the EU single market, the one thing that might meaningfully improve Britain’s growth prospects. Instead she restricted herself to repeating the government’s red lines ahead of its proposed reset of EU relations. Fears that this reset is not really going to amount to much will not have been eased by this report by Tim Shipman in the Sunday Times which suggest the government’s economic objectives are limited to familiar demands for a veterinary deal, a linking of emissions trading schemes, touring rights for musicians and mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

How much of this is negotiable is an open question. Starmer’s presence at the EU leaders informal dinner in Brussels on Monday was supposed to kickstart the reset with progress toward a defence pact. But even this may now have become - inevitably - hostage to demands by EU states that Starmer pre-commit to a new deal on EU fisheries and a youth mobility deal. It is starting to look as if Starmer has indeed fallen into the Cameron trap. Like his unfortunate predecessor, he may end up getting very little - and at a high political cost.

3. Merz’s Bad Bet

I wrote last week about how the imminent German election is unusual because what matters from an economic perspective is not just who wins but how well the losers perform. That is because it will require a two thirds majority in the Bundestag to reform the debt brake that almost all economists agree has itself become a giant brake on the German and European economy.

Unfortunately the chances of achieving that two thirds majority lengthened sharply as a result of the decision by Frederick Merz, the leader of the centre right Christian Democratic Union, to break the post-war taboo in German politics by trying to push through parliament a controversial bill restricting immigration with the support of the far right AfD. The bill was ultimately narrowly defeated in the Bundestag but the repercussions are sure to continue to reverberate through German politics for the remainder of the campaign.

Merz was gambling that by taking such a hardline on immigration, he can halt the drift of right-wing voters to the AfD. But as so often when mainstream conservatives appease the populist right, the opposite looks more likely. Not only has AfD continued to rise in the polls, now standing at 21 percent, second behind the CDU on 29 percent, but Merz’s gambit has damaged his own authority.

As Politico noted:

Twelve conservative lawmakers did not vote, revealing a deep rift within Merz’s alliance and embarrassing the candidate at a critical time in the campaign. Earlier this week, Merz’s conservative predecessor, former chancellor Angela Merkel, condemned his decision to accept far-right support.

“I consider it wrong to abandon this commitment and, as a result, to knowingly allow a majority with AfD votes in the Bundestag for the first time,” Merkel said in a statement.

Merz’s indulgence of the AfD will complicate the task of forming a post-election coalition, which in any case will find it hard to govern if the strong support for populist parties makes it impossible to reform the debt brake. But Merz’s actions last week cross another Rubicon, in addition to the breaking the long-standing firewall against working with the far right. His new immigration agenda amounts to a clear breach of EU law. As Euractiv explained:

The CDU leader has committed to implementing an explosive five-point plan, laid out in his motion, “on Day 1” if he becomes chancellor. If enacted, Germany would permanently reinstate border checks and indiscriminately turn away all irregular arrivals, including asylum seekers – a “de-facto freeze of admissions”.

In the eyes of his opponents, it means that “the largest country in the EU would openly violate EU law like only Viktor Orban has done previously”, as the incumbent chancellor, Olaf Scholz, told lawmakers on Wednesday.

It is true that such laws would stand no chance of making it into a coalition agreement and becoming official government policy. It is also true, as The Economist notes, that ten EU member states are currently taking advantage of a Schengen Treaty emergency clause to conduct temporary border restrictions, though in almost all cases these amount to very little.

But the fact that the largest mainstream party in the EU’s largest member is now advocating a policy that runs directly counter to EU law can only embolden the far right across the EU and lead to more internal border restrictions. Meamwhile Merz’s impetuousness sends a worrying signal that Germany after the election may not provide the stable, pro-European leadership that many are hoping.

4. A French Budget at Last?

As Germany’s politics looks more chaotic, could France be heading for some respite from its own months of turmoil? Francois Bayrou, the country’s fourth prime minister in two years, announced on Saturday that he will next week try to force through the long-delayed 2025 budget using the emergency procedure under section 49.3 of the constitution. That gives parliament 24 hours to bring down the government in a vote of no confidence or the budget becomes law.

This was the high stakes procedure that led to fall of Michel Barnier’s short-lived government last year. Bayrou may have a stronger chance of getting a broadly similar deal through thanks to the decision by the Socialist Party, guided by former president Francois Hollande, to adopt a more cooperative stance in return for some concessions. Even so, the vote is far from a foregone conclusion, as Julien Huez explains in this informative post on his French Dispatch Substack.

Of course, Bayrou’s budget will do little to tackle France’s debt problems. The government says that the budget will deliver a deficit of 5.4 percent this year, down from 6.1 percent last year but is still likely to be too high to meet EU fiscal rules. Barnier had been targetting a deficit of 5 percent. But it goes without saying that should Bayrou fail to deliver the budget and his government fall, French politics would be plunged into an even deeper crisis. That raises the spectre that President Emmanuel Macron himself might have to resign to break the impasse - a level of turmoil that Europe can do without.

5. Hail the Jevons Paradox

I wrote last weekend about the remarkable breakthrough of DeepSeek, a Chinese AI developed that appeared to have created a chatbot that performs as well as any US rival at a fraction of the cost. This news prompted a large sell-off in the markets on Monday as investors contemplated whether the US is falling behind China in the AI race and whether the AI revolution will require much less investment on computing power and energy infrastructure than previously assumed. Nvidia, the AI chip maker, lost $600 billion in a day.

Of course, by the end of the week, much of these losses had been reversed as the market rapidly acquainted itself with the Jevons Paradox, which holds that the further the price of a resource falls, the greater the demand. In this case, the market had convinced itself that cheaper AI would mean the swifter development of innovative applications and therefore greater demand for AI. As you were!

In truth, it was hard to draw any definitive conclusions about the implications of DeepSeek’s breakthrough since we still don’t know the answer to the central mystery highlighted here last week as to how it was achieved: was it due to innovation, chip smuggling or simply theft of OpenAI’s intellectual property?

Nonetheless, Goldman Sachs is adamant that last week’s correction is not the start of a bear market, let alone the bursting of a US tech bubble:

Most bear markets are triggered by expectations of falling profits driven by fears of recession. Our economists remain confident about world growth and remain above consensus on their forecasts for the US, putting the probability of recession in the next 12 months at 15%.

At the same time, while acknowledging that the US market is “priced for perfection”, Peter Oppenheimer, the investment bank’s chief equity strategist, says that the extraordinary performance of the leading US tech companies “does not represent a bubble based on irrational exuberance but is rather a reflection of superior fundamentals”.

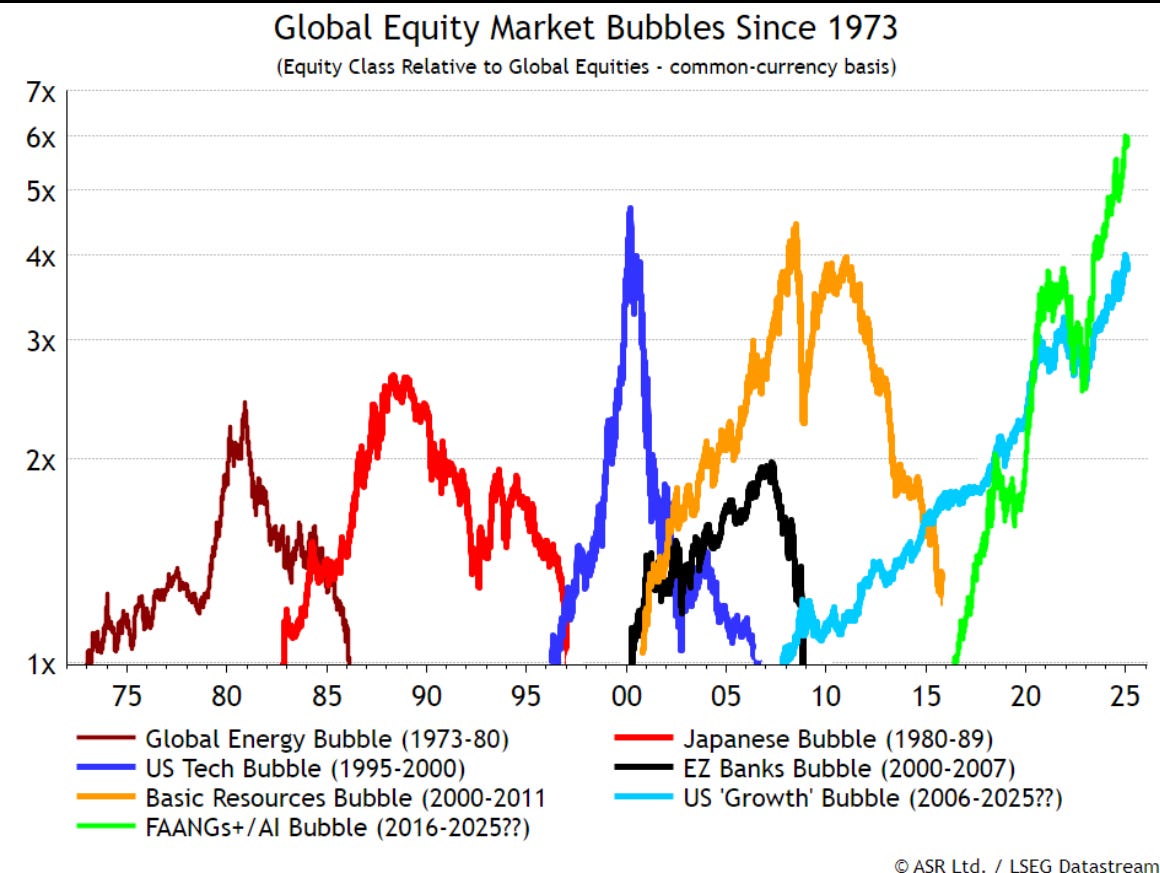

Even so, it is hard not to look at this chart from Ian Harnett at Absolute Strategy Research looking at stock market performance during past episodes of irrational exuberance and wonder quite how much perfection is being priced in. As Harnett wrly notes, “of course, this time will be different”.

Intensified imperialist competition between competing capitalist blocs drives two closely related developments.

Trade wars, executed by states acting as the executive arm of ‘their’ capitalist ruling class, and on the other hand an accelerated arms race.

Trump’s demand for allies to hike military spending up to 5% of GDP is unprecedented in peacetime, and could be delivered only by means of an all out attack on the living standards of of the affected working classes, and on what little remains of the public service infrastructure in health, transport, and education.

Finally, these developments are chillingly familiar. They can be mapped onto the history of the belligerent states in the years and months culminating in the beginning of WW1 in August 1914.

Do Trump's tariffs amount to an American Brexit? Where, the hubris of American exceptionalism leads it to conduct trade wars with its nearest neighbours and biggest trade allies all because it believes it deserves a 'better deal'?

Because, we all know how that worked out for Britain.