Hard Truths

Thoughts on the state of Britain including is the chancellor guilty of market abuse, potential good news for gilts, the myth of Benefits Street, and some welcome Brexit apostasy

Here is this week’s newsletter. A warm welcome to new subscribers. Thanks as always to the generous paid subscribers whose support makes this worthwhile. Apologies that this post is all about Britain when there is so much else going on in the global economy and markets, but I may come back with thoughts on other issues later in the week. Please do share this with anyone you think may be interested. And if you can afford it, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. I look forward as always to your comments and feedback. And please do email me if you have questions or ideas for future posts.

Reeves in the Dock: Market Abuse?

Fiscal Drag: Gilty Pleasures

Welfare Splurge? Benefits Street

Brexit Apostasy: Reality Bites

A few thoughts on the state of Britain in the wake of last week’s budget:

1. Market Abuse

By common consent, Rachel Reeves presided over the most chaotic build-up to a budget that anyone can remember. Now the aftermath is proving chaotic too, not because the budget measures themselves are unravelling but because of the allegation that the chancellor misled the markets and the country.

One City grandee told me on budget day that he thought that ministers should be investigated for market abuse given the impact that all the leaks and kite-flying had on share and bond prices over the previous weeks. That was before it emerged that Reeves already knew that the Office for Budget’s Responsibility’s final forecast would show that the government’s fiscal black hole had evaporated when she gave a press conference designed to roll the pitch for tax rises.

It is hard to argue that the Treasury’s claim that it decided against raising income tax rates days after that press conference because of a better OBR forecast was anything other than misleading. The gilt market had taken fright because it feared Reeves would miss her fiscal rules. The chancellor may have been right to argue that the income tax hike was not needed. But she took the decision because she had realised that this particular kite was not going to fly as Labour MPs made clear their opposition to the breaking of a manifesto commitment.

It is hardly surprising that opposition parties are demanding her conduct be investigated. Even if Reeves survives this latest row, a few points are worth noting:

trust in her judgement and honesty - already dented by previous broken pledges and allegations about plagiarism and misrepresenting her CV - has been badly damaged. Having presided over one very poorly received budget and one chaotic one, no one in the markets or business will be looking forward to her next fiscal event with anything other than trepidation.

the fact that she was unable to push through her preferred option of a 2p income tax rise, having twice been forced to backtrack on proposed welfare cuts, raises big questions about her political authority. The budget did just enough to satisfy the bond markets on the fiscal rules and Labour MPs on welfare, but the lack of proposals for wider reform was striking

to the extent that this row raises further doubts about her political survival - and that of the prime minister - markets are bound to ask who might replace them. The likelihood must be that Labour shifts further to the left, creating further uncertainty. Political instability is bad for economic stability.

the government’s willingness to float the possibility of a 2p income tax rise, only to drop it days later, leaves lingering questions over the future of tax policy. Is an income tax rise now permanently off the table, or will it come back on the agenda if the current fiscal headroom proves inadequate?

the whole imbroglio raises serious questions about the quality of the British state. The practice of budget kite-flying is not new. But those with long institutional memories are incredulous at recent events. Civil servants cannot tell ministers what to do, but did officials try to warn ministers of the risk that their briefings might be creating false markets and were ignored, or did officials simply fail to spot the dangers? Neither bodes well.

2. Gilty Pleasures

For all the sound and fury in the media about the supposed return of soak-the-rich tax and spend, what was striking was how little it altered the trajectory of the economy. As Wealth of Nations noted last week, the budget was in reality a damp squib (see Buying Time). Two new pieces of analysis support this view.

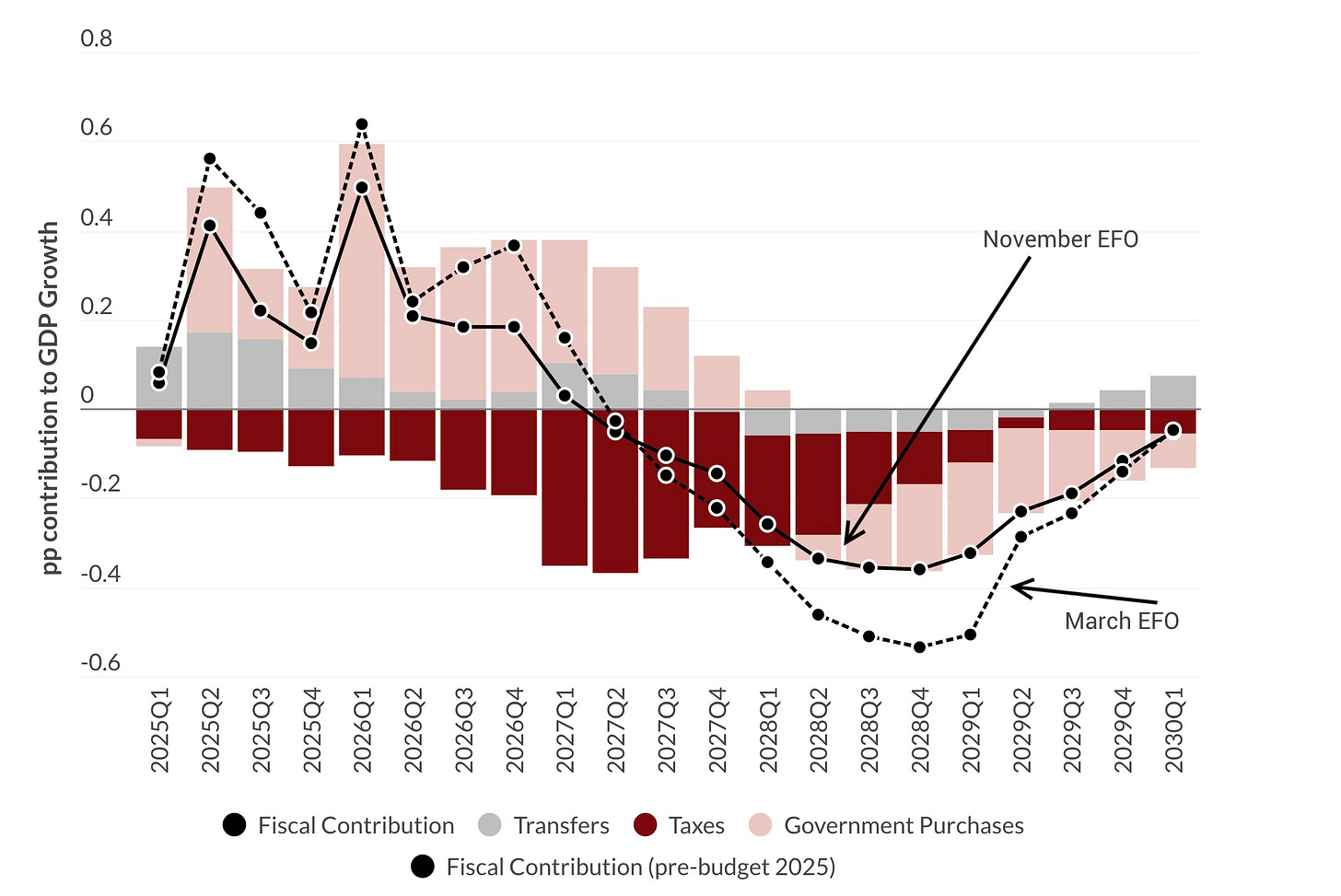

The first comes from an interesting blogpost by David Aikman and Benjamin Caswell for the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR), summarised in the chart below. He has constructed a useful model which looks at the likely overall impact on GDP growth relative to potential growth of Labour’s fiscal policies over the course of the current parliament. In other words, is the totality of Labour’s tax and spend policies adding or subtracting from GDP.

Two observations immediately leap out. The first is that the budget makes very little difference to the trajectory that was already firmly baked in. The second is that while fiscal policy will in fact deliver a modest boost to growth over the next two years, it will become a significant drag starting in 2027, wiping 0.4 percentage points off growth by 2027, which is nearly a third of the OBR’s estimate of UK potential growth. That reflects the impact of income tax threshold freezes, slower growth in government spending and flat capital expenditure.

Aikman’s analysis raises an important question: if fiscal policy is acting as a drag on growth, then what will make up the shortfall? The answer must be a compensating increase in private demand. That in turn suggests that interest rates will need to be cut well below the neutral rate at which monetary policy is neither expansionary or contractionary, which is widely assumed to be somewhere between 2.5 and 3.5 percent. As things stand, the market currently expects one more rate cut in December to 3.75 percent followed by two next year.

Indeed, the authors reckons that the OBR forecast may implicitly be relying on expectations of much lower interest rates for its rosier-than-expected growth forecast even if it doesn’t say so:

One of the more eye-catching features of the November EFO is the sharp fall in the household savings rate embedded in the projection. That decline does a lot of heavy lifting in supporting private demand even as fiscal drag builds. But it raises the natural question: how does the savings rate fall without a material easing in monetary conditions?

Of course, when the Bank of England might respond to this fiscal drag by cutting interest rates and by how much is hard to say. One consequence of the BOE’s long-standing timidity in the face of the persistently sticky inflation shock is that inflation expectations are still nearly twice the BOE’s target (see Frightened Old Lady). That may be a reason for it to be cautious.

But notwithstanding my concerns that Reeves has still not left enough headroom to fully address market concerns over Britain’s fiscal frailty, the implication of NIESR’s analysis is that gilt yields could have further to fall.

3. Benefits Street

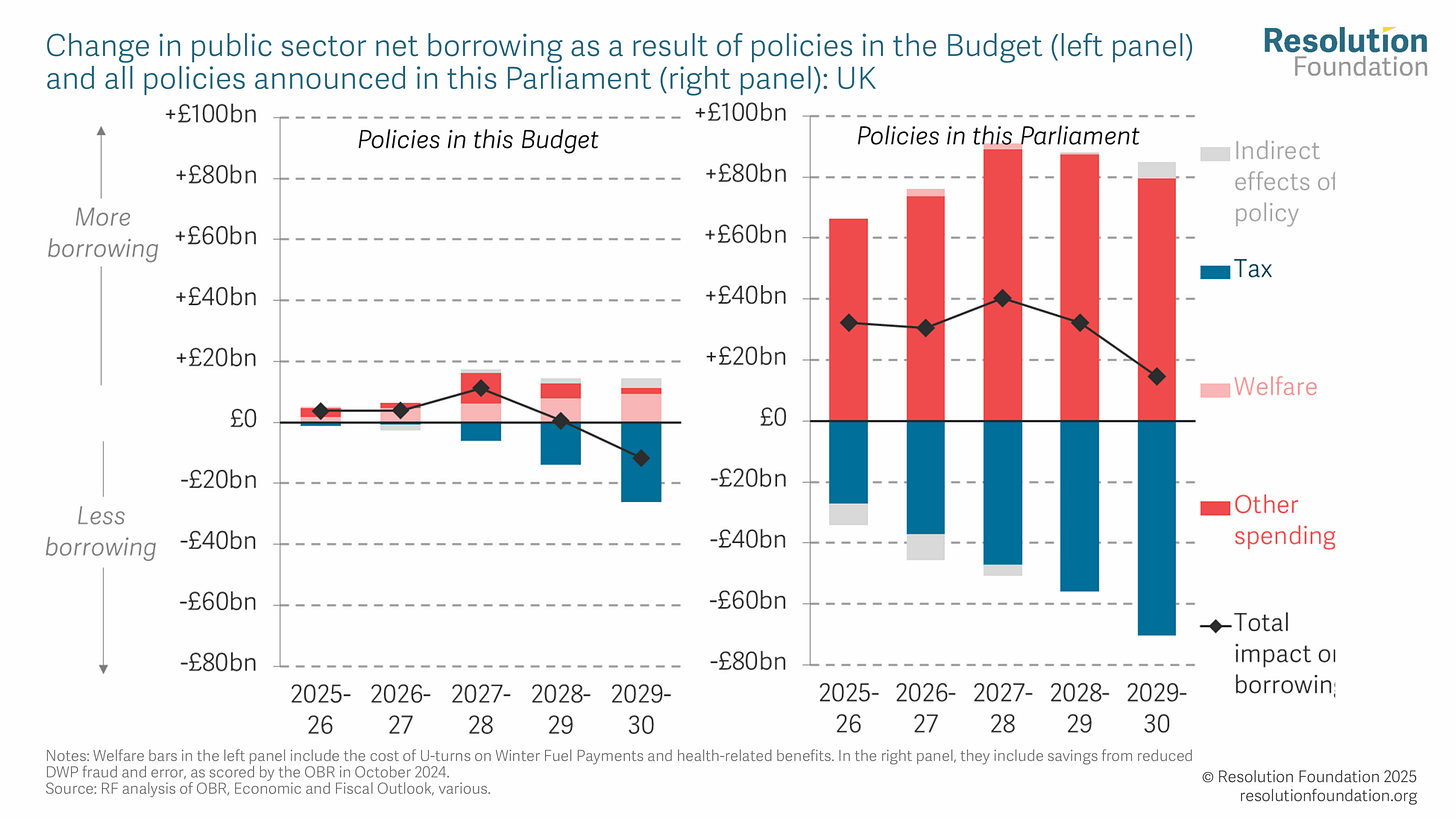

The other piece of analysis that caught my eye comes via a blogpost by Ruth Curtice, the chief executive of the Resolution Foundation and is summarised in the chart below. What it shows is the scale of new welfare spending measures (the pink bars) announced in this budget (the left-hand chart) and across the whole of this parliament (the right-hand chart).

Again, two observations immediately leap out. The first is that increased welfare spending - primarily the abolition of the two-child benefit cap - only accounted for a minority of the tax rises announced in last week’s budget. Most of the announced tax rises were build headroom under the fiscal rules. The second is that over the course of the parliament, increased welfare spending only represents a tiny fraction of increased government spending. In fact, it is almost impossible to see the impact on the chart at all. That’s because the expected increase in welfare spending amounts to just £0.7bn in 29-30.

This puts paid to the notion that the government is engaging in a giant welfare splurge, or that it was a budget for “Benefits Street” as Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch claimed, a line enthusiastically parroted by the right-wing press. Big picture taxes and borrowing are going up to pay for higher departmental spending, not welfare. In fact, much of the hysteria in the media over a supposedly out-of-control welfare system is misplaced. In an column in the FT a few weeks ago, Chris Giles set out some much-needed perspective:

Costs are not spiralling. Projected total welfare payments, at around 11 per cent of national income a year, are lower than when David Cameron was prime minister even though there are more pensioners. Total working-age benefits within the government’s welfare cap — including all out-of-work and health-related benefits — will be well below 2010s levels even after Labour’s U-turn on cuts to disability benefits. Going back further, total non-pensioner benefits have hovered between 4 and 5 per cent of GDP for over 40 years.

What about the 6.5 million people claiming out-of-work benefits that we keep being told about - a number that Department for Work and Pensions figures show to have increased 80 per cent since 2018? Giles again:

This is almost entirely a product of counting the same stuff differently. A higher state pension age lowers overall welfare costs but also increases the number of “non-pensioners” claiming sickness benefits who would otherwise be on the state pension. Universal credit counts many recipients as out of work while the previous benefits it replaced did not.

Professor Ben Geiger of King’s College London has attempted to produce a consistent picture of out-of-work benefit receipt and found that “the current level of out-of-work claims is not any kind of record; it’s similar to 2014-15 levels, and noticeably lower than 2013”.

That is not to deny that there are problems with Britain’s welfare system that will need to be addressed over time, including the spiralling cost of pensions promises and those claiming out of work benefits for mental health issues. But the wider problem is that Britain doesn’t collect enough tax to pay for the size of state that it has become clear over many decades is the revealed preference of its citizens. This was highlighted in a recent post by Erik Fossing Nielsen of Independent Economics at the height of the panic over the French budget:

On World Bank data for 2023 (the most recent year available on a fully comparable cross country basis)… the French state spent 3.8% of its revenue on interest payments. At the peak in 1994 (before the euro’s arrival) the ratio was 7.2%. Both are well below the 9.0% the UK spent of its revenue on interest payments in 2023 (vs a peak of 9.9% in 2011), reflecting that the UK takes in a whopping 13pp of GDP less in taxes than France.

The joke has long been that Britain’s problem is that it wants European levels of public spending but only wants to pay US levels of taxes. The hysterical reaction to last week’s relatively modest budget measures suggest that the British political and media class and voters is a very long way from resolving this dilemma.

4. Brexit Apostasy

Of course, there is one way in which the UK is becoming less European and that relates to the ongoing consequences of Brexit. Barely a day goes past, even nine years after the referendum, without new evidence of the damage caused by that monumental act of national self-harm.

In the last week alone, we had news that British car and van production sank to its lowest level in October since 1956. The industry produced just 602,000 vehicles in the first 10 months of the year, down from 1.7 million in 2016. We also learned that the UK government had failed to agree terms for British participation in the EU’s €140 billion defence fund in a blow to the UK defence industry.

Brexit was the largely unacknowledged ghost haunting last week’s budget. The damage it did to the supply side of the economy was key to the OBR’s substantial downgrade of its estimate of the UK’s long-term potential productivity growth, which in turn left a £30 billion hole in the fiscal forecasts. Brexit is costing the Treasury £90 billion a year in lost tax revenues, according to an analysis by the House of Commons library.

Meanwhile a new study for America’s National Bureau of Economic Research, led by a team of distinguished international economists drawing on macro and micro data, concluded that Brexit has already caused far more damage than the 4 percent of GDP that most economists had previously assumed it would cause over the long-term:

These estimates suggest that by 2025, Brexit had reduced UK GDP by 6% to 8%, with the impact accumulating gradually over time. We estimate that investment was reduced by between 12% and 18%, employment by 3% to 4% and productivity by 3% to 4%. These large negative impacts reflect a combination of elevated uncertainty, reduced demand, diverted management time, and increased misallocation of resources from a protracted Brexit process.

The implication, of course, is that not yet five years after Britain formally left the EU, there is sure to be more damage to come. Yet even now, there remains little political and media discussion of these costs. As far as I can tell, The Independent was the only UK newspaper to carry a news report on the NBER study. That’s why it was good to see this piece in The Times by Ryan Bourne, a former member of the Economists for Brexit advocacy group, in which he acknowledged that Brexit has had harmful economic consequences:

Brexit was a constitutional choice about where laws and regulations were made. My judgment was that Britain’s messy parliamentary democracy would be more effective in error-correcting than Brussels’ bureaucracy, in the long run. But thus far, we have endured Brexit’s downsides, through new trade frictions and protracted uncertainty, with any upsides paling in comparison.

I don’t blame Bourne (with whom I used to co-habit the same page in The Times every Thursday until a new editor decided my contributions were inconvenient) for getting it wrong in 2016. He was young and had fallen into bad company, lured down the rabbit hole of Britain’s myopic right-wing think-tanks. He has since established himself as one of the more insightful conservative economists based at the Cato Institute in Washington.

But the reality is that very few prominent advocates of Brexit have been brave or honest enough to admit any error. A rare exception is Peter Oborne, the distinguished political commentator who was promptly sacked by the Daily Mail for his apostasy. The mainstream media remains dominated by unrepentant Brexiteers along with those who have learned to keep their heads down.

This refusal by much of the media to acknowledge reality is a real obstacle to addressing the very real problems facing Britain. As Bourne notes:

Brexit did not cause Britain’s growth malaise, but it undoubtedly deepened it. Nor did it create our fiscal woes, although it worsened them too. Denial about this helps no one. Indeed, a successful sovereign economic policy demands taking responsibility and facing the world as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Of course, acknowledging that Brexit has been a disaster for Britain begs the question what is to be done about it. I will return to this in a post shortly.

As a European, an anecdote about Brexit: here in Italy, "young people who spend their summers in London (and perhaps stay because it offers more opportunities)" had become a huge phenomenon before the referendum. Today, London has little appeal for the generations finishing high school, and even less for recent graduates.

And if they try to learn more about the UK, they find Farage treating Europeans the same way Salvini treats Africans here.

Great analysis as ever, but can I just point out that there’s something slightly odd and potentially confusing about the way you word one aspect of the Brexit section.

You refer to the HOCL estimate of lost tax revenues, and then go on to say “It therefore hardly comes as a surprise that a new study for America’s National Bureau of Economic Research, led by a team of distinguished international economists drawing on macro and micro data, concluded that Brexit has already caused far more damage than the 4 percent of GDP that most economists had previously assumed it would cause over the long-term”.

But it is really the other way around: the HOCL analysis is *based* on the NBER study. So it’s more a case of the HOCL analysis hardly coming as a surprise, since it’s derived from the NBER study.

Keep up the good work!

Chris Grey