How The West Was Lost

China spent decades laying its rare earths trap. Then Donald Trump blundered straight into it. Now there is no way out. Some thoughts on how we got here, and what happens next

Here is this week’s newsletter. A warm welcome to new subscribers. Thanks as always to the generous paid subscribers whose support makes this worthwhile. It is hugely appreciated. This post is all about rare earths because I think it is interesting and important. I have made it free to read thanks so please do share with anyone you think may be interested. And if you can afford it, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. I look forward as always to your comments and feedback. And please do email me if you have questions or ideas for future posts.

Trump’s Epic Miscalculation: The world’s dumbest trade war

Laying the Trap: Beijing’s cunning plan

Asleep at the Wheel? Too little, too late

Barriers to Entry: Why the West loses

Clutching at Straws: Bessent’s bravado

The earth seems to have tilted on its axis over the past week. Six months after Liberation Day when Donald Trump launched his global trade war with the goal of Making America Great Again, a realisation appears to have descended on the US administration that America - and by extension the West - may be losing.

What has discombobulated Washington is Beijing’s decision on October 9 to introduce stringent new restrictions on the export of rare earth elements (see China’s Chokehold). How far this has unnerved the US government is clear from its response which has veered from comically belligerent to plaintively reasonable. One moment Trump was threatening to impose 100 percent tariffs on China. Days later, and after a sharp stock market sell-off, he took to social media to play down the row: “Don’t worry about China, it will all be fine!”

Scott Bessent, the Treasury secretary, began the week sounding similarly martial: “We will not let these export restrictions and monitoring go on,” he told Fox Business on Monday. “They have pointed a bazooka at the supply chains and the industrial base of the entire free world.” Bessent even launched a bizarre ad hominem attack on a Chinese trade official, Li Chenggang, suggesting he was a “slightly unhinged” economic diplomat who had gone “rogue”. The next day, he was dangling the prospect of a long-term truce if China halted the new curbs.

Bessent’s complaints are obviously laughable coming from an administration that has been weaponising the global trading system since the day it took office. Indeed, as Wealth of Nations noted last week, the new Chinese rare earth curbs are modelled on America’s own Foreign Direct Product Rule restrictions that US government’s have been using to try to hold back China’s technological development for years. Indeed, the new curbs were only introduced in response to a massive expansion by the Trump administration days earlier of its “entity list”, which restricts US companies from exporting to designated Chinese companies.

What lies behind the alarm in Washington, rightly shared in other western capitals, is partly the realisation that, as I noted in my latest column for Euractiv, these new restrictions are a dagger aimed at the heart of Western advanced technology manufacturing and in particular the defence sector. Rare earth magnets are used in most advanced weapon systems from F35 fighter jets to Tomahawk missiles, and there are very few parts of the US high tech defence supply chain that do not contain some trace of Chinese rare earths.

But the alarm also reflects growing recognition that the Trump administration is guilty of an epic miscalculation. In its enthusiasm for weaponising every US chokepoint from finance, to technology to security, it failed to notice that China had not only had acquired its own chokepoint - but was willing to weaponise it too. And there is little that the West can do to counter it.

1. Trump’s Epic Miscalculation

To see how badly the Trump administration miscalculated, one only need look at the words of Marco Rubio. Days after taking office in January, the incoming Secretary of State sat down for a wide-ranging interview with Megyn Kelly of the Megyn Kelly show to discuss the new administration’s foreign policy priorities. At one point, Kelly asked Rubio to elaborate on a statement that he made in his confirmation hearings to the effect that the world would look very different in 10 years if China got its way. His answer was highly revealing:

So, I mean they today control – I mean, we love our technology and we need it for all kinds of advances. All of that depends on critical minerals, at the end of day – ranging aluminum, cobalt – you name it. They have gone around the world buying up mining rights, and they control not just the mining of it but the refining and the production of it, and the use of it for industrial purposes.

So if they decide we’re going to cut you off from these things, they – we’d be in a lot of trouble, because we gave away our industrial capacity on those things. That can’t continue. That’s a vulnerability that we face. And they will use it as leverage. In fact, they are already using it as leverage. For the first time ever, they have actually imposed export controls on critical minerals to damage the – our national security, but ultimately our technological capacity as well.

So it ranges topics, but ultimately if China controls the means of production for both raw material and industry, then we’re – they have total leverage on us economically. And that’s the world we’re headed to. And I was wrong; maybe not in 10 years. Maybe in five.

In fact, it turned out that Rubio was even more wrong than he thought. Just two months later, Trump announced his Liberation Day “reciprocal tariffs” on 57 countries, including an extra 34 percent tariff on all imports from China. But while the rest of the world responded with diplomatic protests and offers to negotiate, China alone retaliated, defying Trump’s threats of escalation. By April 11, both sides had raised tariffs on each other by 125 percentage points in a series of tit-for-tat hikes in what amounted to a mutual trade embargo.

And yet it was Trump who blinked first. Within weeks, reports started emerging of American, European and Japanese carmakers having to shut down production because of a shortage of rare earth magnets. Beijing had used the leverage of its new export controls exactly as Rubio had feared. At a summit in Geneva on 12 May, both sides agreed to remove the new 125 percent tariffs for 90 days, while China agreed to speed up the granting of rare earth export licences.

The two sides met again in London in June amid US complaints that rare earth deliveries were still too slow. This time, China committed to speed up export permits in return for a US commitment to relax controls on the export of advanced semi-conductors. But Beijing made clear that this concession was only for six months, pending a wider trade agreement.

The upshot of China’s brinkmanship is that while Trump has since imposed huge tariff hikes on the rest of the world, raising the average US tariff rate to the highest level since the 1930s, tariffs on Chinese imports remain where they were on the morning of Liberation Day. No wonder Beijing is gloating. An official commentary in the People’s Daily on October 4 stated:

This year, in the face of the US imposition of so-called ‘reciprocal tariffs,’ we had the courage to fight and the skill to fight, and took multiple measures to support enterprises affected by tariffs… Through our actions, we have shown the world that the great ship China is a formidable ‘economic aircraft carrier,’ undaunted by storms and always forging ahead.

How Trump could have blundered into this trade war despite knowing that Beijing possessed this chokehold is a mystery that future historians will no doubt be debating for years. Perhaps he was so confident in America’s superior power that he simply didn’t believe that China would dare to deploy this weapon.

Perhaps he could not believe that a market so tiny could have such outsize geopolitical significance. After all, the global rare earth elements market in 2024 was just $8.42 billion. That compared with a global energy market of $1.2 trillion, a global precious metals market of $1.1 trillion and a global agriculture market of $0.81 trillion. Even the coffee market is 30 times the size at $256 billion.

Yet this miniscule market turns out to be the most important in the world and China’s overwhelming dominance of it gives Beijing huge leverage over the West.

2. Laying the Trap

What makes Trump’s miscalculation more remarkable is that Beijing has never made much secret of what it was trying to achieve. As far back as 1992, Deng Xiaoping had identified the global strategic advantage that China’s bountiful rare earths deposits might confer on the country, famously declaring on a visit to Inner Mongolia: “the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths”.

At that point, America and China’s output of rare earths was broadly similar. But China could compete on price, thanks to cheap labour, government subsidies and a lack of concern for the environment. Indeed, the US was only to happy to outsource this dirty work to the Chinese, who were able to buy up US companies and transplant their technology. By 2010, the extent of China’s chokehold was already clear when Beijing withheld supplies of rare earths from Japan over a territorial dispute in a move that brought the Japanese car industry to a standstill.

Of course, that first Chinese embargo should have set alarm bells ringing across the West. It was the first evidence that Beijing was prepared to weaponise its dominance of global supplies for geopolitical ends. But while Japan itself vowed never to leave itself so vulnerable again - its manufacturers began holding enough rare earths in inventory to meet up to two years of their own needs and they invested in Australian suppliers - the US and the rest of the developed world failed to take any steps to insulate themselves from future embargoes.

That was partly because the more technologically advanced West was focused on extending its dominance higher up the value chain. Indeed, even at the start of this year as it launched its trade war, the Trump administration was still betting, like the Biden administration before it, that American supremacy in the top-end semiconductors needed to train AI models was a far more potent chokepoint.

The West’s complacency also reflected the extent to which China’s rare earths had found their way onto the global market despite the embargo via bootleg exports. But Beijing acted swiftly post-2010 to increase its control of the supply chain. A crack-down on illicit sales meant that state-controlled dealers became the sole suppliers. The mines were nationalised and consolidated into a single state-run company, China Rare Earth Group. China also invested heavily in the processing of critical minerals, where today it has a near global monopoly.

In 2015, Beijing made its intentions explicit. Its Made in China 2025 strategy made self-sufficiency in critical minerals a strategic priority. In addition to developing its own capabilities and resources, China began securing access to mineral resources in the rest of the world, not least in Africa, which holds about one-third of global reserves. Today, for example, China owns approximately 41% of Africa’s cobalt production thanks to its presence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and 28% of Africa’s copper production through mines in DRC and Zambia, according to a 2024 report by the African Climate Foundation.

In 2020, President Xi Jinping went further still. In a speech, he stated that it was important for national security to build up China’s lead in industries where it has an advantage. He called for “intensifying the dependence of international industrial supply chains on China, forming a powerful capacity to counter and deter deliberate supply cutoffs by foreigners.”

Yet in the following four years, China only tightened its grip on the global market. Today it controls around 70 percent of rare earths mining and more than 90 percent of processing. What’s more, it has extended this dominance to the processing of other critical minerals. Much of the world’s cobalt and nickel, for example, is now sent to China for processing. When the US government recently sought to finance the expansion of a rare earth mine in Brazil, it discovered that most of its output had already been contracted to China for processing. Meanwhile Beijing has imposed strict regulations around the export of complex processing technologies, making it even harder for competitors to emerge.

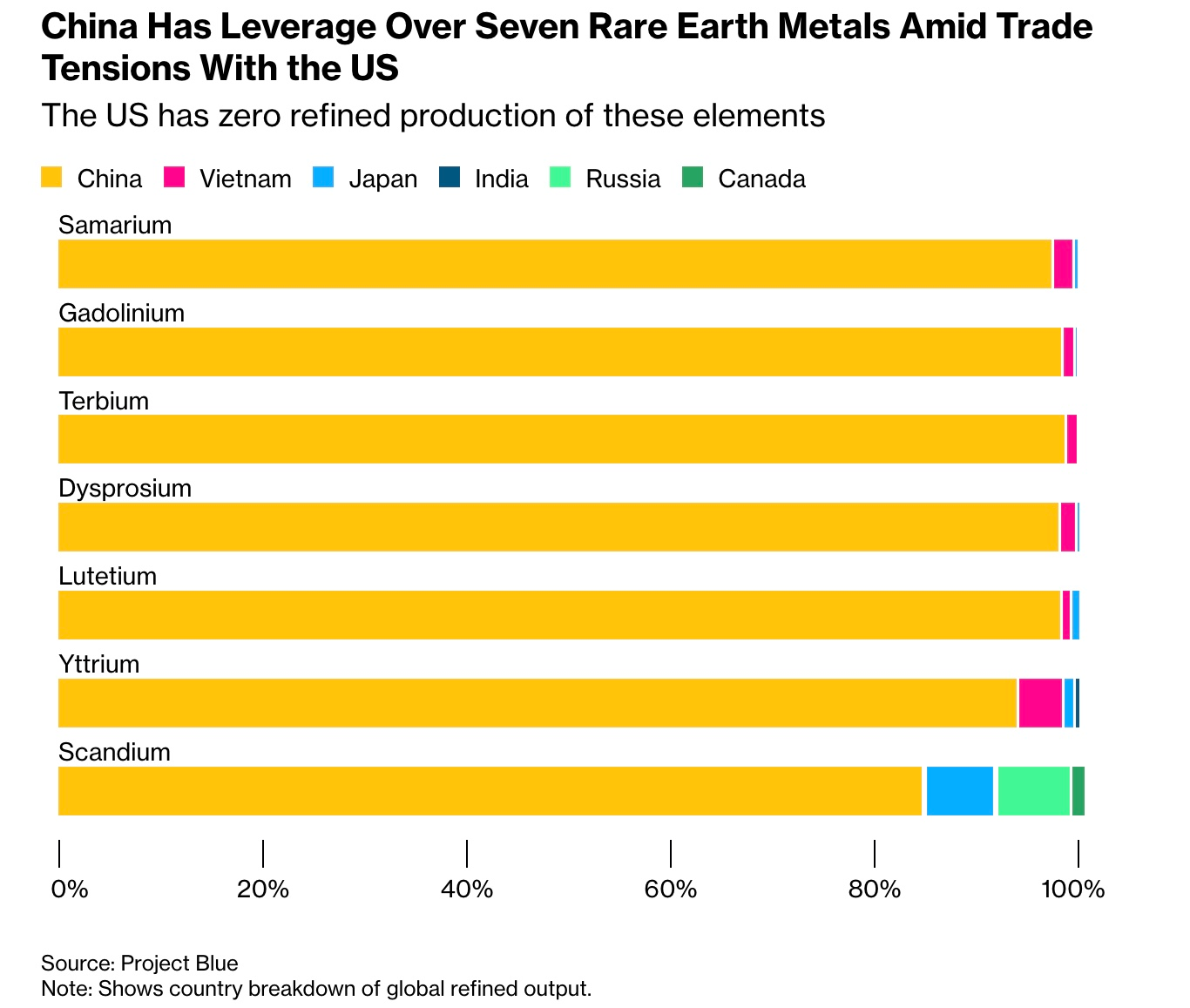

The chart below from Bloomberg illustrates the scale of China’s monopoly:

3. Asleep at the Wheel?

How can the West have failed to develop its own supplies of rare earths and other critical minerals over the past decade during which China has been extending its market dominance and signalling its motives so clearly? This collective failure is even more extraordinary when one considers that demand for critical minerals is forecast to soar in the years ahead, driven by the transition to clean energy.

Yet it would be wrong to suggest that the West has been entirely asleep at the wheel. The issue of critical minerals has been rising up the collective western agenda for years. In 2018, Trump had ordered the US government to draw up its first list of critical minerals and develop a strategy to secure them. The Biden administration drew up a mine-to-magnet rare earth supply chain strategy aimed at meeting all defence requirements by 2027.

The new Trump administration has gone much further. In July, the federal government took a 15 percent stake in MP Materials, the owner of the Mountain Pass mine, America’s only rare earth mine, and signed an agreement to buy 100 percent of its production. More recently, it has acquired 10 percent stakes in Lithium Americas, whose Thacker Pass mine is expected to become the largest lithium operation in the western hemisphere when production begins in 2028, and Trilogy Metals, which is exploring for minerals in Alaska.

Trump has also made securing access to critical minerals central to US foreign policy too. Ukraine was bullied into signing a critical minerals deal with Washington as the price of ongoing US support in its war with Russia. Trump also claimed to have secured mineral rights as the price of brokering peace between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. In September, the US and Pakistan signed a $500m memorandum of understanding to build a poly-metallic refinery and develop rare-earth deposits. And of course, access to minerals is key factor in Trump’s continued interest in annexing Greenland.

The EU has been active too. In 2024, it passed its Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which set a goal of collectively mining at least 10% of the bloc’s total consumption of critical minerals and processing a minimum of 40% by 2030. Since 2021, the bloc has signed 13 raw material agreements with a number of countries, including Canada and Kazakhstan.

More recently, it has identified 47 “strategic projects” to extract, process and recycle critical raw materials across member states. It is committed to streamlining permitting processes so that they will not exceed 27 months for mining projects and 15 months for other processes, down from five to 10 years today. “We do not want to replace our dependence on fossil fuels with a dependence on raw materials,” EU Commissioner Stéphane Séjourné said recently. “Chinese lithium will not be the Russian gas of tomorrow.”

Meanwhile, Australia, currently the world’s fourth-largest producer of rare earth elements, is on track to triple its output of mined rare earth oxides between 2025 and 2027, though currently almost all of its output goes to China for processing.

Yet even with the intense focus on boosting supply chains, it will take years to bring new capabilities online. Currently, there is no heavy rare earth separation capacity in the United States, though efforts to build this capability are underway, notes the Centre for Strategic and Intelligence Studies. Even when MP Materials reaches full commercial production of rare earth magnets at the end of this year at its factory in Texas, it will only produce in a year what China produces in a day.

4. Barriers to Entry

There are good reasons why the West has found it so hard to make inroads into China’s dominance of the critical mineral supply chains. In a panel discussion earlier this year hosted by the Council for Foreign Relations, Dr. Gracelin Baskaran, the director of the Critical Minerals Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, set out some of the reasons that had complicated the development of America’s own resources:

Finding viable projects: lots of factors determine whether a mining project is economically attractive: how deep are the deposits? What is the ore grade? What other deposits are found alongside them? One reason why the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is the focus of much global attention right now is that its mineral deposits are often found at soil level rather than miles underground. Plus deposits of cobalt, whose price is currently low, are found alongside high grade deposits of copper, whose price is very high.

Regulation: on average in America it takes 29 years from the time a deposit is identified to the start of mining; that compares to 18 years globally. What’s more, the process of opening a mine in the US is complicated by the need to acquire up to 30 permits at local, state and national level, some of them duplicative, with differences for federal and non-federal land. Trump’s new National Energy Dominance Council aims to speed up that permitting process

Vertical integration: the West has not invested enough in the entire supply chain from extraction to processing. There’s no point investing in a mine if the minerals have to be shipped to China for processing. Beijing has made securing control of its supply chain a key focus of its foreign policy and has banned the export of processing technology to maintain its chokehold

Infrastructure: a successful mining operation requires more than a hole in the ground. It requires energy and transport links. America currently doesn’t have anything like the energy to mine and process cost competitively, particularly given soaring demand for energy from AI. One reason why so much of North America’s aluminium refining is done in Canada, much to Trump’s annoyance, is due to its abundant cheap hydroelectric power. Meanwhile just one percent of rural areas in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a major focus of western mining interest, is electrified.

Price: Can western suppliers of critical minerals compete with China on price? Carmakers, who are among the biggest buyers of rare earth magnets for EVs, will seek the cheapest possible suppliers, regardless of origin given that most currently lose money on EVs. As David Abraham of Boise State University notes, China can produce a kilogram of dysprosium, the material that turns super strong magnets into heat resistant ones that can go into high-tech goods from robots to EVs, for under $250. Replicating that supply chain elsewhere would cost billions—and still result in higher-cost material.

Demand: the market for many of these critical minerals, particularly rare earths, is tiny compared to most commodities. So anything that expands that market helps to improve the commercial viability of new operations. And by far the biggest source of demand is from carmakers. China has a huge advantage because of the scale of its EV sector - an industry in the US that Trump has effectively hobbled. Indeed, Trump’s war against clean energy is a significant obstacle to efforts to create a viable US industry.

Skills: China has now spent decades developing these industries and growing markets during which time western skills have atrophied. China has nearly 40 universities specialising in extractive metallurgy and another 40 in mineral processing; the U.S., zero. The result is that today, US universities produce around 600 metallurgy graduates a year, compared to around 12,000 in China.

Meanwhile the West suffers from two further handicaps that make it harder to compete with China. The first is that western companies, unlike China’s state-backed entities, need to be able to generate commercial returns. Not only are Chinese firms shielded against industry cycles, they can even exploit their dominance to influence prices. America’s only cobalt mine, for example, opened and closed in 2023 following a steep fall in prices. Similarly, BHP had to close its nickel mine in Australia and Glencore its mine in New Caledonia after a collapse in prices. Chinese firms can drive their competitors out of business.

Second, western firms must comply with strict environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards when investing at home and abroad. Indeed, the Minerals Security Partnership, a 23-country alliance promoted by the Biden administration to try to bring forward new sources of supply, put respect for ESG standards at the core of its guiding principles. Chinese firms are not so constrained. Perhaps not surprisingly, one of the first acts of the new Trump administration was to dismantle key parts of the US ESG apparatus, not least the suspension of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, something previously highlighted by Wealth of Nations (see Trump’s Green Light for Bribery).

5. Clutching at Straws

For now, the best hope is that China’s new restrictions are simply a bargaining chip ahead of a meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping on the margins of the APAC summit in South Korea at the end of the month. Certainly Trump has expressed optimism that a deal can be reached between the two sides. But Beijing intends to use its leverage to drive a had bargain, reckons GaveKal:

So, what are China’s negotiating objectives? The main ones are a rollback of some US technology export controls, a wider path for Chinese companies to invest in the US, a more predictable and consistent set of rules governing trade and investment with the US and probably lower tariffs—although this objective seems less important than the other three; Chinese firms have adapted surprisingly well to a high-tariff environment.

What’s more, as in May and June, Trump may have little choice but to reach a deal. While the US undoubtedly has powerful chokeholds itself that it can weaponise, these come with very high costs that Beijing has calculated - so far correctly - that the US cannot bear. Trump himself conceded last week that the threatened 100 percent tariffs are “not sustainable”. At a time when investors are jittery about a possible AI bubble and deteriorating credit quality in the bond markets and banking system, the US economy can ill afford a market rout.

Nonetheless, a complete climbdown by either Beijing or Washington is unlikely. The fact that both sides have embodied their latest export restrictions in new regulations, which they have justified with reference to national security, means that the best that can be hoped for is that both sides agree to suspend their implementation while they hammer out a wider trade deal. GaveKal again:

It is most unlikely that the rules will be taken off the books. To paraphrase Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, the technology control guns will from now on always be loaded and on the table. The question is how often they will be discharged.

That suggests that the West will need to redouble their efforts to build an alternative supply chain for rare earth elements and other critical minerals. As Bessent acknowledged last week, that may mean having to take a page out of Beijing’s economic playbook by taking more stakes in US companies and setting price floors. “When you are facing a non-market economy like China, then you have to exercise industrial policies,” Mr. Bessent told CNBC.

For Europe, this creates a further problem. Without the capacity to pursue similar industrial strategies, Europeans may find it even harder to build their own supply chains amid a global scramble for resources. The UK was dealt a brutal reminder of what the future has in store this last week when British miner Pensanna scrapped plans to build a rare earths refining facility in Yorkshire in favour of the US, citing increased government support. The danger is that Europeans cannot escape their dependency on the two superpowers.

But no amount of bravado on the part of Trump and Bessent can hide the fact that it will be years - perhaps a decade - before the West can fully wean itself off its reliance on China’s rare earths. That gives Beijing powerful leverage which it clearly intends to exploit as it seeks to extend its lead in technologies of the future and to prevent other countries joining an anti-China coalition. No wonder Trump is rattled. What a tragedy that he did not see where his coercive tactics were likely to lead before he launched the world’s dumbest trade war.

The rare earth disaster is one of the West’s own making due to goofy environmentally driven regulation. Trump is rectifying those tragic mistakes aggressively and taking away the beverage his predecessors foolishly gave away to China. With proper deregulation and support of this key strategic asset, we will reclaim our independence from communists. This Administration is all about reclaiming independence from our Communist enemies, both domestic and abroad, who have sought the destruction of life as we know it across three centuries running.

I’m impressed how Trump and his administration suddenly have begun to talk about the democratic world as an entity…