The State of Britain

Thoughts on Rachel Reeve's uneasy reprieve, Labour's credibility trap, how (not) to grow an economy, Britain's lost competitiveness, breaking the Brexit omerta and advice for Kemi Badenoch

Apologies for the lack of a newsletter last week due to another bout of illness. I wouldn’t normally send out a post focused entirely on Britain, but after the market-driven gyrations over the last week or so, there were various aspects to the mini-crisis that I was keen to explore. Besides, I’ll post again in the next couple of days given the various events unfolding elsewhere in the world. This post is free to read so do please share with anyone who might be interested and encourage them to subscribe.

In this newsletter:

Reeves’s Reprieve: When bad news is good news

Labour’s Credibility Trap: Chancellor-in-a-box

How (Not) to Grow an Economy: Labour’s Pick n’Mix Approach won’t work

Britain’s Lost Competitiveness: the worst is yet to come

Breaking the Brexit Omerta: advice for Kemi Badenoch

1. Reeves’s Reprieve

Some good news at last for Rachel Reeves after the beleaguered UK chancellor’s grim start to the year. UK government bonds (gilts) have just enjoyed their best week since July, while the stock market has hit a record high. Indeed, the gilt market has been Europe’s best performing government bond market this year.

Too bad that the sharp fall in gilt yields followed a one percentage point rise since mid-December to the highest 10 year yield since 2008 and highest 30 year yield since 1998, or that what sparked the rally was a raft of weak inflation and growth data that shows the economy is stagnating. But stagnation beats stagflation since it holds out the prospect of faster interest rate cuts. Relief all round.

The gilt rally provides Reeves with some respite, helped by the fact that her opponents and media critics overplayed their hand with calls for her to cancel a trip to China, deliver an emergency budget, and even for her to be sacked. The UK was not on the brink of a Liz Truss moment. At no point did the gilt sell-off become disorderly, auction demand remained strong, sterling fell slightly against the dollar but hardly at all on a trade-weighted basis, and yields rose in lockstep with those in the US. Indeed, if anywhere is vulnerable to a Liz Truss moment it is surely America which, unlike Britain, looks unlikely to cut its deficit or debt.

Even so, Reeves is not out of danger yet. The yield on 10-year gilts at 4.66 percent is still well above the 4 percent that the Office for Budget Responsibility based its forecast for government borrowing at the time of the October budget. That would wipe out all the £10 billion of headroom that the OBR estimated she had given herself under the fiscal rules at the time of the budget. Given that she has promised to abide by those rules “at all times”, she could now be confronted by a £10.5 billion budget shortfall when the OBR updates its forecasts on 26 March, reckons Goldman Sachs. That will raise some difficult questions:

To fully offset the £10.5bn headwind from higher interest costs, the government would likely have to lower the growth rate of day-to-day departmental spending from 2026 by 0.4 percentage points to 0.9%. But such a large adjustment would not be without difficulties. Most day-to-day spending is protected by existing commitments. The entire adjustment would therefore fall on the remaining “unprotected” departmental budgets, which account for just under a third of the overall envelope. The Autumn Budget plans already imply real-terms reductions in those budgets from 2026 onwards. A further adjustment would imply even steeper cuts, and we think that investors would likely question whether those plans could be delivered.

Of course, Reeves may get lucky. Goldman Sachs reckons the economy is so weak that the Bank of England will cut interest rates four times this year and gilt yields will end the year at around 4 percent. The International Monetary Fund also reckons the BOE will cut rates four times this year although it has just upgraded its growth forecast for this year by 0.1 percentage point to 1.6 percent. When the OBR upgrades its forecasts, there may be no shortfall at all.

On the other hand, who knows what will happen in the US after Monday, when the Trump administration takes over? Bank of America is now predicting that the next move in US interest rates is up, which could send yields above 5 percent. Indeed, it sees a tail-risk that the Fed feels the need to unwind the full one percentage point of interest rate cuts last year, which could sent 10 year yields close to 6 percent. Needless to say, that would cause havoc in Britain and Europe.

Reeves’s fortunes are far from in her own hands.

2. Labour’s Credibility Trap

One thing that makes Reeves’s task particularly hard is that, unusually for a politician, she has an unfortunate habit of boxing herself in. She did this before the election with what was her original sin when she promised not to raise personal taxes. That left her with no good choices for raising the revenues that were obviously going be necessary to tackle the huge spending pressures cynically and recklessly ignored by the Tories. The result was the economically sub-optimal rise in employer national insurance contributions and a raft of smaller tax hikes and spending cuts the infuriated powerful lobbies.

But having boxed herself in once, Reeves has done it again with fiscal rules that are far stricter and harder to finesse than those of the previous Tory government - and to make life even more difficult for herself, ruled out further tax rises. As a result, says Bagehot in The Economist, something peculiar has happened:

In government, pledges designed to make Labour look credible now do the opposite. Measures to bind the chancellor to a steady course guarantee an erratic one. Rules aimed at reassuring voters instead create political hysteria. The chancellor is caught in a credibility trap, where abiding by one promise made in the name of credibility undermines another. The government’s credibility relies on incredible promises that cannot be met.

The risk is that Britain falls back into the kind of debt trap that proved so damaging during Osborne austerity years, in which tax hikes and spending cuts are required to meet an arbitrary fiscal target, which leads to lower growth and lower tax returns, so that further cuts are needed. Rinse, repeat. Meanwhile the deteriorating state of public services acts as its own drag on activity and the debt level never falls low enough to allow higher public investment to be sustained.

As long-standing readers of Wealth of Nations will know, I think Reeve’s reform of the fiscal rules was worse than a mistake, it was a missed opportunity. In her Mais Lecture before she became chancellor, she hinted at one potentially radical idea: a suggestion that she might reform the fiscal rules to focus on public net worth.

This could have ushered in a revolution in the way that the state is managed, based on a ruthless, accounting-driven focus on driving productivity growth to restore the nation’s battered balance sheet. Instead, she bottled it, opted instead for a new version of Gordon Brown’s discredited Golden Rule. The markets rightly saw it simply as an excuse to increase borrowing, subject to supposedly stricter guardrails that have still not been clearly articulated.

One example of why this is likely to prove a missed opportunity was clear from a piece that appeared in The Times over Christmas. It reported that the government is considering a proposal to offer some public sector workers higher pay in return for smaller pension commitments.

It has long been obvious that such a reform is needed. Younger workers clearly do not value their generous pensions, as is clear from the severe recruitment and retention issues in core frontline services, yet the cost of unfunded public sector pensions is a vast long-term liability on the national balance sheet. Already, nearly £1 in every £4 raised in council tax is being spent on staff pensions.

Yet The Times also reports that this proposal is likely to run into resistance from the Treasury given the implications for short-term borrowing. In a world of public net worth, a debate about how to strike a better balance that gives public sector workers higher upfront pay while reducing long-term fiscal risks becomes possible because those unfunded pension obligations would be included on the balance sheet. Instead, bad accounting leads to poor decision-making.

3. How (Not) to Grow An Economy

One reason that the mood in Britain is so dark is that Reeves has lost control of her own narrative. Labour’s defining “mission” was supposed to be growth which it was going to achieve by delivering three things that had eluded the Tories: an investment boom fuelled by reform of the planning system; productivity growth driven by reform of the public sector to drive productivity growth; and improved trade as result of a reset of the relationship with the European Union.

Yet Labour’s actions in office have suggested it has other priorities. As I noted in my latest column for Byline Times, the party of the workers needed to show it could be the party of capital. Instead, Reeves hit businesses and providers of capital with higher taxes and increased costs. She gave public sector workers generous pay settlements without securing changes to working practices. Instead of taking on powerful vested interests that are holding back productivity growth, she picked a fight with farmers. For all the talk of a reset with the EU, the government appears reluctant even to agree to a youth mobility deal.

To regain the confidence of business and investors, Reeves needs to prove that growth is still Labour’s priority. But that may be easier said than done. That’s because, as Ben Ansell, professor of comparative democratic institutions at Oxford University, argues in this interesting post on his Political Calculus substack, Labour lacks a clear theory of how to grow the economy.

There are no shortage of models of economic growth in the academic (and not-so-academic) literature for Reeves to choose from. They include:

Neoclassical growth, which Ansell calls “Osbornism, which essentially relies on creating a sound saving and investment environment

Neokeynesian Growth, which is roughly the model favoured by Gordon Brown and allows a bigger role for government, both through active demand management and investment in things that improve productivity such as technological innovation and skills

Developmentalism, which is inspired by state-led industrialisation strategies in China and elsewhere in Asia and is the favoured model of the Labour left and was also reflected in President Joe Biden’s green new deal

Schumpeterian Growth, which emphasises creative destruction as a result of technological innovation and whose arch-exponent in Britain in recent times was Boris Johnson’s former adviser, Dominic Cummings

Supply-Side Growth, which emphasises tax cuts and deregulation and is highly influential on the political right, being most recently associated in Britain with the doomed premiership of Liz Truss

Labour’s problem is that to the extent Reeves has a growth strategy, it borrows from each of these approaches, even though they are not obviously compatible. It seems to combine a George Osborne-style approach to the public finances, a Gordon Brown-style approach to public investment, a Corbynite/developmentalist approach in Ed Miliband’s net zero push, a Cummings-esque disruptive approach to AI, and a Trussite “supply-side, rip-it-all-up approach to planning”.

The thing about different theories of how the world works is that they are… well… different, often incommensurate. You can’t treat grand, clashing economic schools of thought like a jaunt through Woolworths pick and mix. You have to make a choice and direct the bulk of your policy in that direction. As I said last time out, to govern is to choose. Not just to do something (though that has been a problem) but also among distinct economic strategies.

When a government is resorting to asking cabinet ministers and regulators to come up with growth ideas after just seven months in office, as Labour has been doing, it is hard to feel positive about the next four and a half years.

4. Britain’s Lost Competitiveness

For an even more bracing take on Britain’s growth challenges, this piece by Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at Oxford University, sets out the challenges clearly. His core argument is that if the government wants to take economic growth seriously, then it should focus on (the lack of) UK competitiveness.

It needs to ask itself why UK exports lag, why imports grow, and why domestic production is so expensive. It also needs to ask why saving are so low and why investment is overwhelmingly foreign.

The government needs to ask itself how the sprint to net zero electricity by 2030 is going to make its energy more competitive, and why building more houses is going to help British companies compete. It has to ask itself why unfunded public expenditure is going to increase UK investment and why increasing the taxes on employing people is going to make UK companies more competitive.

Instead of making the usual declaration that the UK is going to be the (not even “a”) world leader in not just AI, but in net zero technologies and hydrogen and nuclear, and in all the sectors picked as “winners” in its emerging industrial strategy… the government should first start with much more basic questions: why would global companies want to relocate to the UK; why is manufacturing industry very much on the exit path; and why is it so much more attractive to set up businesses elsewhere, including in the US?

Helm’s answers to his own questions are that the dash to net zero electricity and building 1.5 million new homes by 2030, with their clear “whatever it costs” implications, will not make Britain more competitive. Instead, they will drive up the cost of energy, of wages, of materials, of capital and, in the absence of policies to boost domestic savings, make Britain even more reliant on foreign capital (“the kindness of strangers”.

His solution? Scrap unachievable 2030 net zero and housing targets, push the costs of the energy transition onto UK citizens via increased charges while keeping industrial energy costs low, increase personal taxes to pay for increased NHS and defence spending, while cutting taxes on business and saving to encourage investment.

Of course, all of this would force UK citizens to stop living beyond their means, which is why no government would willingly do this. On the other hand, says Helm, the current economic set-up in the UK and many other countries, notably in Europe, is not sustainable and so will not be sustained:

The path to rebasing is inevitably very painful, and this government is not going to do it ex ante. No government looks likely to do so. The consequences of not doing these things cannot be avoided. They will happen ex post. Things may get worse before they get better, and a fundamental re-set is forced upon us.

Yikes. But I fear he is right.

5. Breaking the Brexit Omerta

If there is one thing that almost everyone agreed upon over the past couple of weeks, it is that the UK is particularly vulnerable to global bond market gyrations. That is partly a reflection of its twin budget and current account deficits, the second largest in the world after America, which leaves it reliant on foreign investors. Nowhere is this reliance more acute than in the gilt market, where foreign buyers account for nearly 30 percent of the market, compared to an average of around 18 percent in other developed markets.

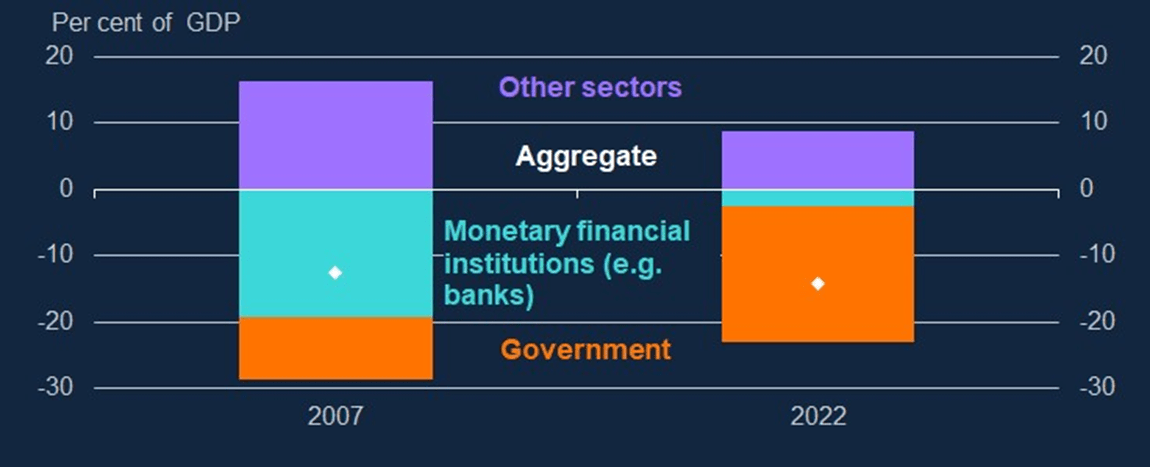

This sharp rise in the share of foreign ownership, even as the size of the gilt market has itself exploded, is relatively recent and reflects big changes in Britain’s economic model. For several decades, this model was based on a simple proposition: it was the best place from which businesses and investors could access the European market. As a result, money poured into Britain’s financial system and corporate and housing sectors from around the world.

But that changed following the global financial crisis and above all Brexit, as the chart below from the Bank of England’s Bank Underground journal shows. Now if Britons are to continue to live beyond their means, they need to fund the current account deficit by selling gilts to foreigners.

This reliance on foreign buyers of gilts is a vulnerability for Britain for reasons that OBR set out in its 2023 Fiscal Risks and Sustainability report:

Overseas holders of gilts are less likely to have a such a structural desire for sterling assets. Instead, gilts are more likely to be seen as just one of a number of government bond assets they hold. As a result, smaller changes in the relative attractiveness of gilts can mean foreign investors quickly switch to other assets in potentially large volumes.

Meanwhile, Brexit continues to damage the UK economy in other ways, not least in its ongoing impact on trade. A new report published this week by the Institute for Public Policy Research sets out the grim details:

Between 2021 and 2023, estimates suggest that EU goods imports to the UK were down by 32 per cent and UK goods exports to the EU were down by 27 per cent compared to what would have happened if the UK had not left the EU.

The UK’s fall in goods trade is not part of a global pattern: while other G7 countries saw an average 5 per cent increase in goods exports by the third quarter of 2023 compared to 2019 levels, the UK experienced a 10 per cent decline by the end of 2023.

In this context, that is why one of the most interesting developments of the week was the decision by Ed Davey, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, to break the long-standing political omerta over Brexit by calling on the government to negotiate a customs union with the EU by 2030. This excellent post by Lewis Goodall explains very well the political significance of the move.

I don’t believe that the customs union proposal is realistic. But it marks the first time since 2019 that a Westminster party has challenged the unhappy consensus around Boris Johnson’s deal. It means that Starmer for the first time faces pro-European pressure to go beyond his red lines in his proposed reset of relations with the EU. It means that Brexit is once again a contested political issue. As in the 1970s, it is hard to see how Britain can begin to get out of its economic funk without much closer relations with the EU, so this pressure is very welcome.

Indeed, almost as significant last week was Kemi Badenoch’s admission that her party had made a mistake in pushing ahead with Brexit without a clear idea what the UK’s new growth model should be. It may have only been a single line in a speech in which the new-ish Conservative leader was seeking to justify not coming up with any policies for the next three years. But it was an implicit acknowledgement both that Brexit has been economically damaging and that Britain still does not have a coherent post-EU growth model.

As Badenoch now goes about the task of trying to come up with coherent plans to address Britain’s many challenges, she will discover that its relationship with the EU will be central to many of them, such as defence, trade, energy, net zero, AI and investment. Indeed, her plans will not be credible unless they are based on a clear understanding with what the EU is doing in any particular policy area.

That is why, in the unlikely event that Badenoch were ever to ask for my advice, my recommendation is that she should make it her priority to reverse David Cameron’s original sin by seeking to rejoin the European People’s Party, if only with observer status. It was the former prime minister’s decision to leave this pan-European centre-right political grouping that signalled his own weakness and helped set his party on the destructive populist path to Brexit.

Nothing would more clearly signal that the Tories were under new management than a decision to rebuild links with sister parties across Europe and to once again play a constructive role in European debates with profound implications for the British national interest. It would mark an overdue return of seriousness in British politics after a 15 year descent down the rabbit hole of Brexitism. It is the sort of signal that might even be noticed by the bond markets.

Obviously I don’t expect this to happen.

On the different economic models, where might joining the EU's custom union fit?

This, in effect, increases the size of the profitable market, but it seems more than just Osbornism - making the investment environment sound?

Speaking as an Australian, I am astonished that any level of UK governments still maintains and use any pension program that has a growing and/or ongoing unfunded liability position. Australia tackled this issue over 25 years ago. The government pension funds that had unfunded liabilities were 'closed to new members'. Existing fund members had their pension rights maintained. New funds were created to provide for new employees/members and real-time contributions were made by the employer to these new funds, hence no unfunded liability position has developed in the new funds. The unfunded liability position in the old funds has been reduced by the sale of some sale of public assets and as time passes, members (and dependents) die and then the unfunded pension entitlements cease.