Witkoff's Peace Plan plus other abominations

Thoughts on Britain's missing millionaires, the troubling economics of territorial conquest, and four bad omens for a divided Europe

A warm welcome to all the many new subscribers over the past week and particular thanks to those who have become paid subscribers. Your interest and support is hugely appreciated. This post is free to read so please do share with anyone you think may be interested. And if you can afford it, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. In the meantime, I look forward as always to your comments and feedback.

In this newsletter:

Britain’s Missing Millionaires: Blame Brexit not Reeves

Witkoff’s Peace Plan: Right of Conquest

Divided We Stand: Four bad omens for Europe

1. Britain’s Missing Millionaires

The big story in Britain this week is Rachel Reeve’s Spring Statement, when the chancellor will update parliament and the country on the state of the economy and the outlook for the public finances. Inevitably, all the media and market attention will be focused on the Office for Budget Responsibility’s fiscal forecasts. Has Reeves done enough with her plans for cuts to welfare and the civil service to restore her fiscal headroom under the fiscal rules? What does the budget watchdog’s latest growth and interest rate forecasts mean for the outlook for public borrowing and gilt issuance? Above all, will the chancellor be forced to break her election promise and raise taxes later this year?

All vitally important questions for those who make their living betting on the short-term political and financial markets. But all something of a distraction from the big picture which is the continued implosion of Britain’s economic model. While it suits partisan political commentators to blame Britain’s struggles with persistent low growth and sticky inflation, which has put the country squarely in the crosshairs of the bond markets, on Rachel Reeves’s budget last year, the real problems go far deeper. Long-term readers will know that this has been a core theme on Wealth of Nations and two items that caught my eye over the last week neatly illustrated the core problem and the worrying lack of serious solutions.

The first was a piece by Camilla Cavendish in the Financial Times on the exodus of rich foreigners from Britain, driven away by Reeves’s abolition of non-dom status. In particular, they are unhappy about a change in the residency rules that means that their families will have to pay inheritance tax on their worldwide assets after their deaths if they have lived in Britain for 10 of the last 20 years. According to Cavendish, Britain has turned from a net importer of millionaires into a net exporter:

Between 2023 and 2024 the numbers leaving more than doubled, according to investment migration advisers Henley & Partners — meaning the UK lost more wealthy residents than anywhere except China. There are many possible reasons: nervousness about Britain’s deficit and sluggish growth, fears of further tax rises, failing public services. But the assault on inheritance comes up in every conversation.

I hear the same complaints all the time too, typically from wealthy expats who have lived and worked in the City for much of their careers but object to being taxed the same way as other long-term residents. I have written before about the important, if under-appreciated role that London’s status as a tax haven for rich foreigners played in the City’s modern renaisance. Anecdotally, it certainly seems as if the tax changes may be prompting some to rethink whether they want to remain in Britain. In a globally competitive market place for talent, other countries are these days making efforts to attract the wealthy.

That said, I am inclined to take some of the wilder claims about the scale of the exodus and its possible fiscal impact with a hefty dose of salt. As this analysis by Tortoise media noted:

Research on previous non-dom changes in 2017 found that exits were low and that tax is not generally a first-order consideration in location decisions. Access to networks, elite schools, cultural activities and corporate interests are all frequently cited as reasons the UK remains “sticky”.

If bankers are leaving Britain, it is because London itself is losing its lustre as activity seeps elsewhere to other financial centres. In that respect, any exodus should be seen as part of a much bigger and more worrying story, which is the slow decline of the City of London and in particular the gathering crisis in the stock market. Last year only 17 companies floated in London and 88 left. The Times reports that the Stock Exchange is lobbying firms at risk of decamping to New York on the “myths” surrounding the US market. It is not the exodus of millionaires that Britain needs to worry about but the exodus of companies.

The latest evidence of this comes via a new research note by Goldman Sachs on the state of the UK Equity market. Like many other banks, Goldman began the year as a bull of the UK stock market, extolling how cheap it is relative to other major markets. But after another three months of underperforming every major market other than the dysfunctional US, it has joined the ranks of those calling for the government to offer tax breaks and introduce new rules to force pension funds to buy UK equities to help shore up domestic share prices.

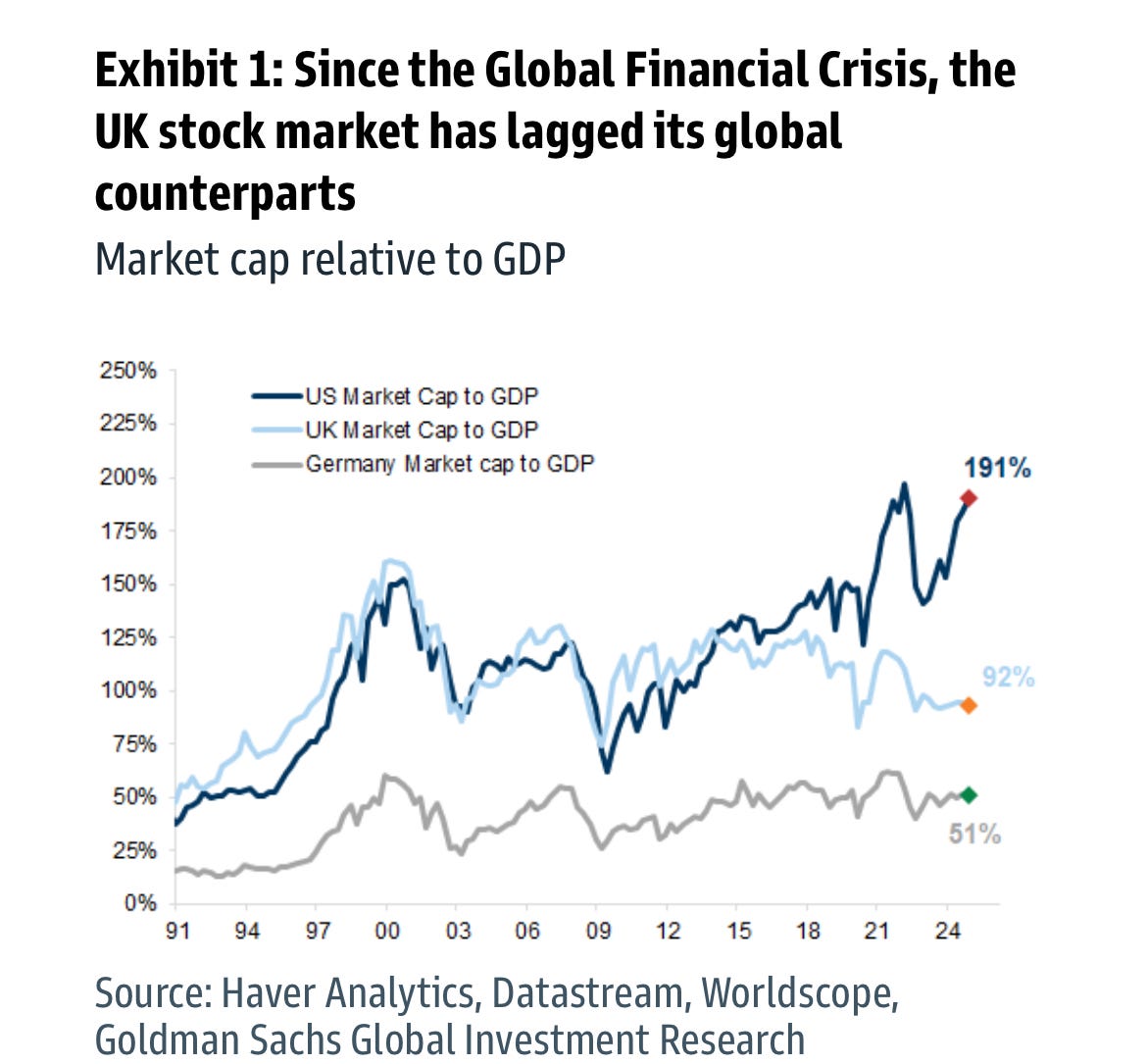

I have written before about why I think this would be a dreadful idea, though I understand why those with skin in the game would argue otherwise. Goldman blames the low valuations of UK listed equities on the low level of domestic ownership of UK equities - a problem which it traces to the Global Financial Crisis as well as regulations that required defined-benefit pension fund and insurers to shift out of equities and into bonds.

The UK market is just one-third domestic-held versus other markets where domestic ownership tends to be 50-90%. UK stocks are valued at a notable discount and we think this is partly because of the need to encourage more foreign buyers to enter the market. Fading demand has resulted in higher buybacks and lower IPOs in the UK. Companies have begun to stay private for longer, while more recently, they have moved listings to the US to benefit from higher liquidity and valuations.

I have explained in previous posts why I am sceptical of this argument. The big de-equitisation by UK institutions was almost entirely complete long before the global financial crisis. And UK households have always been more inclined to invest in property rather than shares. Besides, as Goldman’s own accompanying chart below shows, the London’s underperformance began in 2016, not 2008. That start date tallies with what other charts that I have highlighted in previous posts show too. What might have happened that year to undermine Britain’s attractiveness as an investment destination?

The exodus of millionaires and the decline of the London stock market are best seen as two sides of the same coin: the steady collapse of Britain’s Thatcherite economic model which flourished for 30 years as a result of a serendipitous combination of the creation of a the EU single market, the collapse of the Soviet Union and arcane set of arrangements that made Britain a veritable tax haven for foreigners. That model has now been blown up by a combination of Brexit, anti-money laundering rules, and a political backlash against rising inequality, exacerbated by a cost of living crisis and the collapse of public services.

The problem is that no one knows what new economic model post-Brexit Britain should put in its place. I don’t know either. But what I do know is that there is something deeply dispiriting about Sir Keir Starmer being so desperate for a trade deal with the US to avoid Trump’s tariffs that he is even prepared to contemplate rewriting the tax code to suit American corporate interests, when the one trade deal that would very obviously deliver far greater benefits to the British economy remains bizarrely politically taboo. Brexit continues to cost the country far more in the form of higher trade barriers with the EU than any benefits that a trade deal with America could possibly bring.

Brexit has been a disaster for the City, for manufacturing businesses, for universities, for farmers, for hospitality businesses, for musicians - the list goes on. Last week the German ambassador to the UK proposed that Britain should rejoin the EU’s customs union, or what Brexiteers used to fondly call the Common Market. I used to think such an idea was politically unthinkable. But lots of things that were unthinkable a few weeks ago that have suddenly become thinkable. Certainly I can’t think of a better way to get the bond markets off Reeves’s back. Who knows, it might even give the millionaires a reason to stay.

2. Witkoff’s Peace Plan

The US-led peace talks to end the Russia-Ukraine war are taking place today in Saudi Arabia. For an idea of where they might be heading, it is well worth listening to or reading Steve Witkoff’s extraordinary interview with Tucker Carlson. Trump’s lead negotiator is quite clear that he thinks the core of the problem lies the five Ukrainian regions that he can’t actually name but which Russia apparently now partially occupies.

Witkoff not only seems to accept Moscow’s claim that it has some legitimate claim to these oblasts based on its own rewritten version of post-World War 2 history. He has also accepts the Putin narrative that these regions are legitimately Russian because its inhabitants are Russian-speaking and they “overwhelmingly” backed annexation by Russia in referenda since the current war began.

Leaving aside that this is obvious nonsense, not least because those sham referenda were only conducted in the occupied part of those regions, Witkoff is clear that he sees the key to a peace deal lies in Kyiv, and thus Europeans, recognising Russia’s conquests as legitimate transfers of sovereignty. Whether Witkoff believes that this territorial annexation should apply only to the land currently occupied by Russia or the whole of those oblasts is unclear.

But as the Moscow Times reports, Putin is certain to demand that Kyiv surrender even those areas that Russia has not been able to take by force. And if Witkoff and Trump concluded that such a surrender was the price of a deal, who would bet against them using every facet of US leverage to force Kyiv and the Europeans to acquiesce? The fact that Witkoff accused European talk of providing peacekeeping forces as “a posture and pose” and implicitly accused Sir Keir Starmer of wanting to play Winston Churchill only underlined the complete disdain for European concerns in this negotiation.

Regardless of whether a deal is achievable, America’s apparent willingness to legitimise Russia’s demands for territorial conquest breaks one of the most important taboos that has underpinned the international order since the second world war. Indeed, America is doing its own bit to undermine the norm with its increasingly menacing threats against Canada, Panama and Greenland. The uninvited visit to Greenland today by Mike Waltz, Trump’s national security adviser, and Usha Vance, the vice president’s wife, combined with JD Vance’s astonishingly hostile comments towards Denmark on Sunday, will only add to concerns that America is eyeing its own territorial conquests.

That is bound to have significant ramifications for global security and the global economy. In an interesting essay in Foreign Affairs, Tanisha Fazal, Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota, sets out how the erosion of the norm against territorial acquisition could play out over the coming years. In the first instance, she says, it makes it more likely that other revisionist states will test the boundaries with smaller-scale moves against weaker states:

Azerbaijan’s 2023 takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh, which elicited a minimal global response, is one recent example. Next, Sudan could seize the Amhara region of Ethiopia. China could adopt a more aggressive posture in the South China and East China Seas. Venezuela is already claiming large swaths of Guyana, and it could act more forcefully on those claims. The Palestinian territories, Taiwan, Western Sahara, and other polities that are not broadly recognized as sovereign states will be especially vulnerable. Even more worrying is the possibility of escalation in border conflicts among nuclear-armed states, such as China, India, and Pakistan.

The danger is that as countries no longer fear major reprisals for territorial aggression, threats that seem far-fetched now could become real possibilities, says Fazal. In particular, buffer states, located between rival countries:

Today, other former Soviet satellite or socialist republics, stuck between NATO and an increasingly revanchist Russia, could face a fate similar to Ukraine’s. If Chinese-Russian relations turn sour, Mongolia, too, could be at risk, as neither of its more powerful neighbors will have any assurance that the other won’t act first to take over the state that separates them. Nepal and Bhutan, likewise, lie in precarious positions between China and India. Kuwait could once again be in danger, situated as it is between the regional rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia.

What’s more, once respect for national territorial sovereignty starts to be eroded, respects for other elements of sovereignty could also start to weaken:

When small island states claim fishing and mining rights in exclusive economic zones, other countries in the region may simply ignore their claims. Might will disregard right. Violations of political sovereignty, from election meddling to regime change, may become not only more frequent but also more overt. Such breaches have always occurred, but norms have somewhat contained them and provided some recourse for weaker states. If the powerful no longer respect the rules, they undermine social restrictions on acts of violence against institutions, land, and people.

Finally, the erosion of the norm against territorial conquest could even precipitate a broader shift in an international system that is built on relations between sovereign states.

Several challenges to sovereignty already loom, such as the threat posed by climate change to small island nations, or the way technology companies have assumed the communication, diplomatic, and military roles once reserved to governments. The return of territorial conquest would add to these pressures. If the survival of a state threatened by an aggressor is increasingly in doubt, that state’s ability to strike security and economic agreements will decline as well. And if state sovereignty becomes broadly precarious, it is not clear how the open markets that underpin the globalized order will operate.

Ironically, this is a risk that Witkoff implicitly acknowledges, elsewhere in his conversation with Tucker. Discussing the prospects for peace in the Middle East, he says that what is motivating Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States above all is the need for security in order to attract finance. At the moment these states are having to finance their development in large part through their own resources revenues. International banks and investors are reluctant to invest, Witkoff claims, because of the security risks of a regional conflict.

That makes it all the more extraordinary that Witkoff and Trump are prepared to be so cavalier with respect to the norm against territorial conquest in Ukraine - or indeed, undermine it with repeated threats to the sovereignty of Canada, Greenland and Panama. The difference seems to be that the Trump administration regards the Middle East as a region of great dynamism and potential, whereas it sees Europe a declining museum economy with little to offer America - or more importantly, them.

3. Divided We Stand

If Europeans want to convince America that they remain geopolitically and economically relevant, they have work to do. It’s true that so far this year, the verdict of the markets has been that Europe has responded positively to the Trump shock. America’s pain has been Europe’s gain. While the Standard & Poors 500 has fallen since the start of the year on fears that tariffs, Elon Musk’s assault on the federal government and the erosion of the rule of law will hit growth and damage confidence in the US, European stocks have rallied in the expectation that increased defence spending would outweigh the damage from trade wars.

Nonetheless, while some rerating of European stocks is certainly justified, along with upgrades to European growth forecasts, the challenges facing Europe are still formidable. A massive Keynesian stimulus in the form of Germany’s vast new defence, infrastructure and climate spending packages, which were ratified by the German parliament last week, will not solve many of the continent’s more fundamental problems. Indeed, some of the difficulties that lie ahead were on full display at the European Council summit that took place at the end of last week.

First, it was troubling that the section dealing with Ukraine policy was signed by only 26 of the 27 members. The EU may be able to gloss over Hungary’s refusal to support Ukraine for now, but the reality is that it could start to become highly problematic, particularly if Trump and Witkoff start making demands of Europe. A particular concern is the future of EU sanctions policy, given that these need to be rolled over every six months. One danger is that Hungary’s pro-Putin and pro-Trump orientation could rob the EU of one of its strongest cards: its say over the future of the bulk of Russia’s frozen assets.

European leaders are already split over whether to seize these assets. While many are now in favour, Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever, whose country is home to Euroclear which holds roughly €200 billion of the €300 billion total, denounced such a move last week as “act of war”. But, as Anton Moiseienko and Yuliya Ziskina note in a paper for the Royal United Services Institute, it only takes one country to refuse to roll over the sanctions when they lapse later this year and those funds will become unfrozen and can be immediately reclaimed by Russia.

That would deprive the EU at a stroke of its largest source of funding for Ukrainian defence, reconstruction and reparations. It would remove what is arguably Europe’s strongest leverage in Ukraine negotiations. It would also undermine the funding of a $50 billion loan to Ukraine underwritten by the G7 that utilised the income from the frozen assets, thus putting taxpayers on the hook. Above all, it would deal a deep blow to EU sanctions credibility:

For all the talk of reparations, accountability, and a tribunal for the crime of aggression, the EU would find itself handing over €200 billion to the regime that launched Europe’s biggest war since World War II. The lesson for all to see would be that European unity has a short lifespan, and any serious adversary can simply outlast EU sanctions.

Second, for all the excitement over Germany’s giant increase in defence spending, it is easy to see why it is causing some concerns in other European capitals, as Politico reports. To deliver this increase, Berlin didn’t just lift its own constitutional debt brake, it convinced the European Commission to rip up the European Union’s fiscal rules almost overnight and without discussion. These are rules that had been debated for years and had not yet been in place for a year.

But while Germany may be able to take advantage of the new dispensation which allows defence spending to be excluded from borrowing limits, some of Europe’s biggest economies including Italy, France and Spain, don’t have that flexibility. Putting most of the burden for European rearmament on national governments is likely to lead to higher borrowing costs and even create fiscal risks. It would be far better to fund common defence via common borrowing. Without this, rearmament efforts - and the fiscal boost - are likely to fall short. Yet having got the reform it needs for itself, Germany appears to be reverting to its customary resistance to common borrowing. There was no mention in the Council minutes.

Third, if the EU is going to have any chance of standing up to a US president who is convinced that the EU was created “to screw the US”, then it needs to be able to put up a united front and carry through its threats. Yet last week, it fell at this first hurdle when it announced that it would be delaying its planned retaliation to Trump’s steel and aluminium tariffs until April 14.

While Brussels says that it needs time to consult with member states, it seems clear that it caved in to pressure from the French wine and spirits industry, which was spooked by Trump’s threat to impose 200% tariffs on all EU alcoholic beverages if, as originally planned, Brussels imposed duties on American bourbon (and other US goods) on 1 April. That in turn points to a wider problem with the EU’s trade strategy, as Thomas Moller-Nielsen writes for Euractiv:

It consists essentially of three prongs: first, repeatedly emphasising that its response will be “firm”; second, doing nothing; and third, seeking an alliance with Washington to combat China’s “overcapacities”, or mass production of cheap manufactured goods.

There is a serious risk that such a strategy could push Europe into a corner. By effectively blaming China for US protectionism, Brussels risks losing out on the opportunity to play Beijing and Washington off against each other – and could end up angering both.

Finally, Europe’s real long-term economic prospects hinge not on increased debt-funded spending but on improving its competitiveness, as the reports last year by Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta set out in brutal detail. The one thing that both former Italian prime ministers agreed upon was the urgent need for the EU to deliver on its long-promised capital markets union, now rebadged as a savings and investment union, whose goal is to develop deep and liquid pools of non-bank finance for European businesses.

Step one of this project was supposed to be the creation of a pan-European securities regulator, a European equivalent of America’s Securities and Exchange Commission, which can drive integration of national savings markets. It is therefore somewhat concerning that even this is a step too far for some, with Ireland and Luxembourg blocking an agreement at last week’s summit. That does not bode well for the many tough structural reforms at both EU and national level that are going to be required to revive the European economy.

Everyone agrees that the Trump shock poses an existential crisis for Europe. But until the EU shows that it is capable of acting as well as talking, of delivering bold steps towards deeper integration, any recovery in the markets or the economy is likely to be limited and short-lived.

Thanks for this, Simon. Your line: "The steady collapse of the Thatcherite economic model" and the lines that followed have captured my imagination and the idea deserves to be picked up elsewhere.

One factor in the steady reduction of UK pension fund commitment to UK equities - and equities in general - that is never mentioned is the closure of DB funds and their increasing maturity. If you are covering the pensions of aging beneficiaries you play safe and stick to bonds. It testifies to your point that this process has been going on for decades.